Above: Title card from the 1994-1995 television sitcom, "All-American Girl."

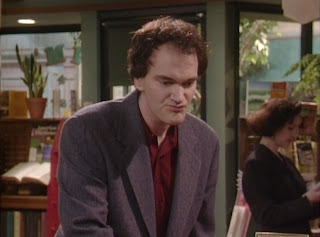

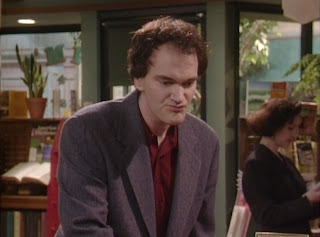

After achieving massive commercial and critical success with 1994's

Pulp Fiction, a 31 year old Quentin Tarantino appeared on a 1995 February Sweeps episode of ABC's "

All-American Girl," the short lived sitcom starring his friend, Korean-American comedienne Margaret Cho.

Above: "Pulp Sitcom" mock title card.

The episode in question was called "Pulp Sitcom," which originally aired on Wednesday, February 22, 1995. The episode was the season's second to last, and ultimately, the penultimate episode of the series (which would be canceled later that year after a period of limbo). More an extended comedy sketch than a true situational comedy episode, "Pulp Sitcom" recreates a number of the more famous scenes in Tarantino's magnum opus, all in the context of Cho's Valley Girl-like protagonist's relationship with Tarantino's pop culture obsessed character.

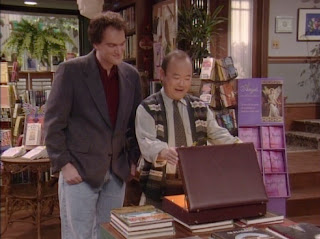

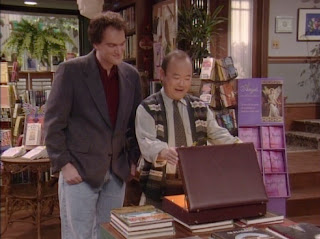

Above: Desmond (Tarantino) and Benny (Kusatsu) look in the briefcase.

The episode's plot is as follows: Desmond Winocki (Tarantino) is the video supplier to the retail book establishment of Benny Kim (

Clyde Kusatsu), the father of the sitcom's protagonist, Margaret Kim (Cho). Winocki walks in to Kim's store to deliver a briefcase containing some videos he had requested. Desmond places the briefcase on the table, and he and Benny open it. Light shines from the interior of the brief case just as it did

Pulp Fiction. From it, Desmond hands Kim a copy of

Dorf Goes Auto Racing and a reading light, revealed to be the source of the mysterious glow. Thereupon, Margaret enters the room and is introduced by her father to Desmond. The two briefly discuss movies, leading Desmond to say, with proper irony, that the film

Speed (released the previous year), was "a little violent for my tastes."

Above: Margaret Kim (Cho) attempts to draw a square.

Desmond then asks her on a date, to which she reluctantly agrees. She explains her initial hesitance to her father, noting that Desmond is, as they say, a square. To illustrate her point, she mimics Uma Thurman in

Pulp by drawing a square in the air. She inadvertently creates a trapezoid instead. But the date is set, and the initial plan is to go to dinner and then return to Desmond's apartment to watch his new "favorite" film, Tim Burton's

Ed Wood.

Above: Desmond (Tarantino) and Margaret (Cho) dance at the Fantasy Diner.

The two venture to Fantasy Diner, a send-up of both TV's "Fantasy Island" and

Pulp's

Jack Rabbit Slim's, complete with a Ricardo Montalban maître d', a crew of mimes, and an Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini waiter. They discuss actress

Debralee Scott (who played Hotzi Totzi on "Welcome Back, Kotter" and Cathy Shumway on "Mary Hartman, Marty Hartman"), leading Margaret to remark that she "wouldn't have taken you for such a culturally aware guy." She orders the

Warren Burger burger and the Pam Grier coffee, while Desmond orders a

Hudson Brothers burrito. As a disco song comes over the restaurant's sound system, the two take to the dance floor and perform a number of silly dances, from the electric slide to the robot.

Above: Desmond (Tarantino) gives Grandma (Hill) a Watchman.

Smitten, she takes him to meet her extended family for a dinner at home. He is not unprepared. To her doctor brother, Stuart (

B.D. Wong), he brings gourmet coffee, to her adolescent brother, Eric (J.B. Quon), he brings a football, and to her grandmother, Yung-hee Kim (

Amy Hill), he brings a Watchman television. Doing his best Christopher Walken impression, he relates to her the great lengths to which he went to obtain the Watchman from a relative trapped in Grenada. When Margaret's mother, Katherine Kim (

Jodi Long) needs assistance determining the temperature of the turkey, he raises a meat thermometer over his head and stabs the turkey just as John Travolta did with the syringe into Thurman's heart.

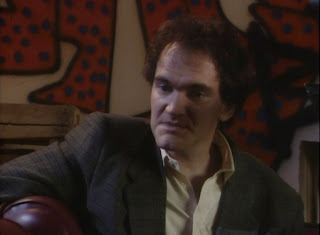

Above: Desmond (Tarantino) explains the perils of a life of crime.

But there's a catch: Upon a second trip to Fantasy Diner, Margaret discovers that Desmond is actually a criminal: he sells bootlegged videotapes, which risks both himself and her father. Cho and her two friends, Ruthie Latham (

Maddie Corman of

The Adventures of Ford Fairlane) and Gloria Schechter (

Judy Gold) worry about the implications of his sinister endeavours. He convinces Margaret to accompany him on his sales route before terminating the relationship, and on so doing, she notes that she feels like she is in "Real Stories of the Highway Patrol." Along the way, Desmond stops at the home of an elderly man (the late

Patrick Cranshaw, who played the part of Blue in 2003's

Old School) to deliver some tapes. But he knows there are consequences to his life of crime: "You get caught moving a hot

Yentl, you go to jail."

Above: The Kim family reacts to Desmond's despondency.

Margaret decides the relationship must end. She tells her father of the ordeal, who asks merely, "What do you mean, I'm selling hot

Cool Runnings?" But Desmond appears at the Kim home and offers to give up his life of video piracy to be with Margaret. While there, he spills tomato juice on his shirt, leading to Mr. Kim, inexplicably wearing a tuxedo, to assume a Mr. Wolf like roll to remove the bright red substance.

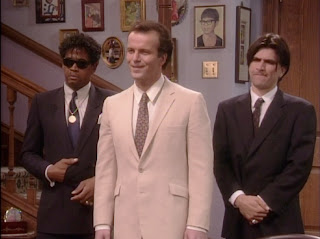

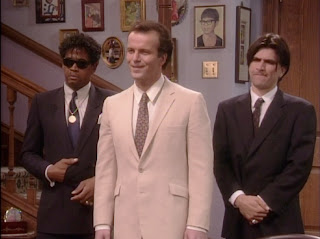

There is only one problem: Average Tony (

Robert Clohessy), Desmond's mobster employer who cannot be convinced to allow an employee to leave, has suddenly appeared at the doorstep with two of his 1970s style goons (dressed like Jules Winfield and Vincent Vega).

Above: Average Tony (Robert Clohessy) and his goons at the Kim house.

Frightened, Grandma Kim ventures down into the basement to find a weapon, choosing first a baseball bat and other options before settling on a samurai sword. Meanwhile, Margaret attempts to reason with Average Tony, who has implied that violence will be wrought unless Desmond returns to his employ. But there's only a few minutes left in the episode, so it turns out that it is just a giant misunderstanding and that Average Tony would never hurt someone over something as insignificant as video tapes.

But it is too late; the police have been called, and Desmond must flee. He makes his escape, pausing to kiss Margaret goodbye before vowing to someday return. Their relationship must have been true. After all, throughout the episode, Desmond refers to Margaret by a variety of nicknames, all deriving from popular breakfast treats: Post Toastie, Crunchberry, Pop Tart, Apple Jack, and Sugar Bear. By episode's end, Margaret calls Desmond her Boo Berry.

Above: Grandma (Hill) confronts the gangsters in her living room.

After the narrative ends, and as the closing credits roll, Tarantino and Cho chat with each other out of character. Tarantino exclaims that he will do "no more episodic television." But then Cho mentions the possibility of his becoming a "recurring character." "Like

Ted Bessell on 'That Girl,'" he asks? No Cho replies, "like

Bookman on 'Good Times.'" The episode ends.

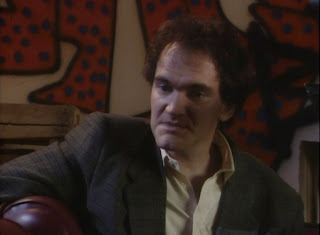

Above: Desmond (Tarantino) makes his appearance early in the episode.

On the DVD, Cho offers a commentary track for the episode, although she remembers very little of its specifics. Instead, she generally shares a few general anecdotes of her friendship with Tarantino and her embarrassment of her 1995 hairstyle. ("I look so strange to myself," she says at one point during her commentary.). Other details were difficult for her to recall; she could not remember the name of the young actor who played her teenage brother on the program. (The commentary was recorded sometime in mid-to-late 2005; Cho references both her 2005 film,

Bam Bam and Celeste, and Tarantino's stint as guest director on "CSI: Crime Scene Investigation," which aired in May of that year.).

Above: Desmond (Tarantino) bids farewell to Margaret (Cho).

Describing "Pulp Sitcom" as an "unusual departure" for the program, she notes that the episode did not address issues of ethnicity and immigrant life, staples for the series. She describes Tarantino as "very good friend of mine" and notes that he was "such a good sport for doing all of this" and that it was "such a coup to get him." Cho praises him for "start[ing] a whole new way of looking at violence" and making cinematic violence "cartoonish" and "fun." (That was also a popular criticism of Tarantino then, as now.). She lamented that he "would never tell us what was in briefcase" but speculates that he himself did not know what was contained therein. (By February of 1995, there were certainly enough theories floating around on the Internet.). She relates a story of worry that took place at the initial table reading of this episode's script. Tarantino was tardy, and those affiliated with the show thought that he, as some sort of "weird bad body of cinema," would stand them up and be difficult. From Cho's commentary, we learn that Desmond's car is Tarantino's own; the 1964 Chevelle Malibu convertible was also featured as Vincent Vega's vehicle in

Pulp Fiction. Cho waxes nostalgic about drives through Beverly Hills and "being very young Hollywood" with Tarantino in those days.

Because this was February sweeps, and because Tarantino was cinema's hottest property at the time, the episode received a fair amount of coverage immediately before it aired. Critical reaction was mixed. Mark de la Vina of the

Philadelphia Daily News, apparently desperate to make a throwaway reference to the

New German Cinema, offered:

Obscure cinematic references aside, the episode is more Ralph Malph than Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Throughout the show, which at times runs like an excuse for Cho and Tarantino to swap '70s pop culture trivia, ''All-American Girl'' cast members ape various scenes from Pulp Fiction. However, the best poke at the movie is by Tarantino himself, especially his parody of Christopher Walken's now-legendary scene where his character explains how he hid a pocket watch when he was in a Vietnamese prison camp.1

Manuel Mendoza on the Dallas Morning News opined:

Too often . . . stunt-casting is a merely an exercise in self-indulgence, or worse, self-parody.

One of the clearest examples is Oscar-nominated director Quentin Tarantino's favor to his friend Margaret Cho - they have a pact that requires them to mention each other during their talk-show appearances. Wednesday, he's on her ABC show, "All-American Girl."

...

The nonstop references to Pulp Fiction and Mr. Tarantino's video-store background are for the most part forced, though the mocking of the movie's Christopher Walken watch scene and Uma Thurman wakeup scene are smile-worthy.

"That's it, no more episodic television," Mr. Tarantino says while credits roll. He must have seen his performance.2

Matt Roush of USA Today wrote:

What was funny in its brashness in Pulp Fiction is rendered feeble by this obnoxious, self-aware parody of the cult movie. It's almost as bad as a Saturday Night Live sketch. Quentin Tarantino, Pulp's trendy writer/ director, misguidedly guest-stars as Margaret Cho's new boyfriend, a spazzy video supplier who consorts with gangsters (one named "Average Tony"). The show spoofs Pulp totems - a glowing briefcase, a weapon in a basement, a dance in a retro diner, an incongruous tuxedo, a meat thermometer wielded like a hypodermic needle - without making them the least bit clever.3

Though the most caustic, the review by Eric Mink of the New York Daily News is perhaps the most accurate (and best stands the test of time). Mink wrote:

One thing is certain: If you haven't seen Pulp Fiction, you won't have a sliver of an idea what's going on in tonight's episode or why the studio audience is laughing. Given the use of laugh-and-applause signs, the studio audience itself may not have known why it was laughing.

I've paid to see Pulp Fiction three times, and I could be persuaded to see it again. I've seen tonight's "All-American Girl" episode once for free come to think of it, I was paid to watch it and I'm not likely to watch it again unless somebody manacles me to one of those A Clockwork Orange rigs where you're lashed to a chair with your head immobilized and your eyes held open with little stainless steel medical pry bars.

...

Yet even these scenes play with the same feeble sense of forced humor that marks the show on weeks when Tarantino is not present. None of the show's able cast is well served by this venture, Cho worst of all. She seems to have been sliced and diced through the Vegematic of network sit-commery and bears little resemblance to the bold, stereotype-busting standup she developed on the road in comedy clubs, college campuses and cable specials.4

So too were the denizens of Usenet worried. On February 20, 1995, just two days before the episode would air, Greg Sorensen, writing on bit.listserv.cinema-l, advised simply: "Be afraid, be very afraid . . ." Replying to Sorensen the following day was Melissa Agar, who attempted to explain:

Actually, Tarantino is friends with Cho and asked if he could be on the show. He is a tv junkie, according to an article I read, and would love to do more guest spots like this.

Apparently the whole thing will be filled with Pulp Fiction references.

FYI -- the character of Lance in PF is loosely based on a bit from Cho's stand-up routine.

(See also here for a March 1, 1995 post on the same subject by Marni L. Hager.). Reached by email over the past holiday weekend, Agar confirms that almost thirteen years after its airing, the episode has failed to remain fully in her memory. She writes:

I really don't remember his appearance all that much. I read the comment I made and don't even remember the things I make reference to. I do remember him being on the show (I was a fan of Cho's work even back then and watched that show religiously) and I was (and I suppose still am) a fan of Tarantino and do remember being really excited that he was going to be on.

It is likely forgetabble because "Pulp Sitcom," along with the series of which it was a part, are mostly forgettable relics of an era of mostly bad sitcom television. "Seinfeld" was at its zenith, but "Arrested Development," BBC's "The Office," and "30 Rock" were all years in the future. The true reinvention of the sitcom was not yet well underway.

Above: Tarantino, out of character, talking to Cho during the credits sequence.

Shortly after recording some commentary tracks for the "All-American Girl" DVD release, Cho

offered some memories of the show on her official site's blog:

The problem with the show was that in the hysteria of this being the first Asian American family on screen, the writing was stuck in an identity crisis. If we are Asians, then are we funny? Are we racy funny or homey funny? Can we do this? Can we do that? Also, there seems to be a cast of thousands. I think it was because the idea of Asians on television was so outlandish that the executives thought to soften the blow by adding kids, parents, older siblings, twentysomething friends, cute white boys, and NO GAYS!!! Can you imagine???!!!

There were lots of people every week. I think I don’t remember a lot of it because I was not really there for any of it. Although it is ostensibly my show, my voice isn’t on it at all, which is a shame. I didn’t really have a voice then though, so my identity and race served as a makeshift ‘opinion.’ I think that is why there hasn’t been another attempt at an Asian sitcom, because the confusing conundrum of race as voice, of ethnicity as identity, prevails. I don’t watch shows because the characters are white or black. I watch for reasons that don’t factor in race. I know that sometimes people like to think that racism is over, but it isn’t. It is just far subtler and harder to identify.

Still, watching All-American Girl is pretty amazing, thinking of all the pressure we were under, and having no real vision of what it should be. It is like a pupu platter of jokes. One of everything, to please the uninitiated palate, an abrupt tutorial in Asian American life as seen by a bunch of innocent bystanders.

Cho echoes these sentiments on the "Pulp Sitcom" commentary, in which she observes that the show's producers simply "didn't understand the things I asked them to do." She also remarks that she "never understood the [sitcom] medium" with its various laugh tracks and that she didn't think she could do such a show in the present day.

Cho also addressed the life and death of her sitcom in I'm the One That I Want, a concert film.

Cho also addressed the life and death of her sitcom in I'm the One That I Want, a concert film.

There is no question that the sitcom was struggling both with the internal issues to which Cho refers in her blog entry but also external pressures from critics. Although it was second in its time slot at the time, it was 55th in the total ratings. Thus, the appearance by Tarantino late in the season during February sweeps may have been a last ditch effort to save the show. Tarantino did his part to promote his appearance. During an "Entertainment Tonight" interview, he quipped, "I'm thinking of giving up this feature film thing. Maybe this could be spin-off material."5 That, after all is what friends do for one another, and Tarantino and Cho were friends, if not more, during this period in the mid-1990s.

In fact, their friendship predated the episode and is what prompted his cameo. They met years before at the Snake Pit in the Melrose section of Los Angeles. ''We had the best time,'' Cho told the Philadelphia Daily News. ''We are just so connected in the ways we think about society and culture."6 On the commentary track, Cho recounts the times that she would watch movies in the Hollywood hills with Tarantino, who had just purchased the entire inventory from the video store at which he formerly worked in his pre-fame days.

De La Vina, writing for the Philadelphia Daily News, quoted Cho as follows:

''It's always hard to explain what our relationship is based on. I admire him so much. And he's such a good friend to me. And a real treasure. He's such a talent and he's just so intelligent and perfect - just everything that I want.''

Including a boyfriend?

Raising her eyebrows, Cho tossed off a knowing glance, yet remained mum.7

Despite her reluctance to confirm a relationship, Tarantino would take Cho as his date (or vice versa?) to the SAG awards that year. Cho certainly romanticized his appearance on her sitcom, calling it their"version of (the Jean-Luc Godard film) 'Breathless,' . . . [w]ith the two lovers on the run, you know, what it might be like, is 'Badlands.'''8 But in the end, even Tarantino could not save the show from cancellation, which it was after a hiatus in mid-1995.

Cho would later complain to Lydia Martin of Knight Ridder about the show's constraints, its future, and the revamp that was to occur before its demise was confirmed:

"I have been criticized very unfairly because of my ethnicity, because I am a woman, because of everything," Cho says. "They want the show to be the be-all-end-all. And that's really unfair."

While Disney producers wait to see if ABC will pick up the show for a second season, they have gone back to the drawing board, stripping Cho of her uptight family and moving her into a place of her own, which she shares with three guys.

If the revamped show airs, it will be kind of like a Four's Company, except Cho gets no Jack Tripper-style ogling from her roommates.

"I think the show will work better that way, because it's a lot closer to who I am," says Cho, who lived with two male roommates for years.

"When you are friends with guys for a long time, the whole gender thing gets lost. You become entities, like they don't consider you a woman at all."9

The members of the cast would go their separate ways. Wong would later appear on HBO's "Oz" with Clohessy. Cho would later appear in a failed pilot with Kusatsu in which she played his wife, as opposed to his daughter. Now a tattoo enthusiast, she has said that Margaret, Marisa Tomei's character from Four Rooms, was based upon her.10

"Pulp Sitcom" is available on the fourth and final disc of All-American Girl: The Complete Series (which was released on DVD in January of 2006 and available here via Netflix). That disc also features the immediately preceding episode of the series, "A Night at the Oprah," featuring guest star Oprah Winfrey and a young, pre-fame Jack Black.

1. Mark de la Vina, "Couple of Hot Prop-erties; 'Pulp Fiction' visits 'Girl,'" Philadelphia Daily News, February 22, 1995.

2. Manuel Mendoza, "Watch star go flying by: Sweeps guest shots aim at ratings boost," Dallas Morning News, February 21, 1995.

3. Matt Roush, "Critic's Corner," USA Today, February 22, 1995.

4. Eric Mink, "'Pulp' Parody's a Cho-Show No-Go," New York Daily News, February 22, 1995.

5. Leah Garchik, "Mirror Mirror, On the Wall, Who is Humblest of Them All?," San Francisco Chronicle, February 21, 1995.

6. Mark de la Vina, supra.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Lydia Martin, "Margaret Cho Hits the Road While ABC Decides Her Series' Fate," Philadelphia Inquirer, April 6, 1995.

10. Marilyn Beck and Stacy Jenel Smith "Shore's Latest Flick is Reshot to Include O.J. Simpson Murder Trial References," Denver Rocky Mountain News, March 29, 1995.